The Type-Safe-Boundary, what it is and how to use it to prevent bugs

Background

I’ve been writing code for some decades now. Over that time there is one thing I have learned through projects that have failed, projects that have been successes, legacy projects, greenfield projects, projects with dedicated experienced teams, projects with fresh new developers, distributed projects, closed source and open source, and all other kinds, being a consultant working with a multitude of companies and open source enthusiast, and that is - strongly typed code prevails.

The concept I am describing below is something I have been using for well over 20 years now, but never got around writing about. So, here it is!!

Strong or weak typing

There has been many discussions pro and con, and I am not opposed to using different kinds of weakly/duck-typed typed languages (or dynamic languages which is a more precise term), but through these discussions there was never a clear distinction on why one way was better than another. That observation, that when people can argue back and forth, all with good arguments, there is something else going on here.

Also, even when writing code in strongly typed languages, one can write in a weakly typed manner, so there is a gliding transition between strong and weak typing. That is actually the essence of this post.

Bugs and weak versus strong typing

Strongly typed code will result in the compiler being able to prevent more bugs, but it often causes you to write more declarations - which may seem to slow down project speed. The successful transition many have experienced going from a language like Javascript to TypeScript (see e.g. Brian Harry’s post on the TFS Web solution), the addition of strong types to a language like Python (another favorite of mine) using MyPy, are more indications that strongly typed features in a language has some clear advantages with respect to preventing, and even finding bugs.

When writing small programs, duck-typing is a very efficient, but as the program grows in size and complexity, it becomes harder and harder to keep track of the types, and bugs starts to appear. Unit testing can help, but thinking of left-shifting as a principle it is better to move this to the compiler, and even better, all the way into the editor and as-you-write type of checking.

Code that does the real business logic is the one most critical with respect to bugs. Anything we can do there to prevent bugs should be done, and that means one should use strong typing as one bug prevention action.

Where to use strong or weak typing

We can set up a couple of rules for this:

- When we access any kind of external access point to the program, the information we work with is very often represented in a weakly typed manner.

- When we’re working deep inside the program, the classes and strongly typed features of the language are more prevalent.

Looking at a larger program

Let us assume a moderate or large size program, and let us assume it is written in a strongly typed language like C#. As mentioned above, there is nothing preventing the developer from using non-strongly typed structures in C#, and that is something we often find and use.

The speed of development is often faster for weakly typed programs, but only in the beginning. As the program grows in size, development slows down, due to lack of clarity in the code, and more bugs seeping in.

The discussions about strong and weak typing often go around these things. Some claim all code should be strongly typed, and are being countered by those working with external access, and vice versa with internal code. Likewise between people working with small programs versus large programs.

As many programs actually go from small to large, and if there is not any attention to these things, the smaller program can grow from a fast fun thing, to a large slow bug-ridden dinosaur. And then, we have the typical large legacy program.

A simple mantra

The code that works with weakly typed, or even more precise, with untyped data, necessarily have to be aspects of weak typing. Code that doesn’t do that, can be strongly typed.

So if you can, use strongly typed. If you must use weakly typed, do so.

Architectural aspects

If we look at some architecture models, like the Onion Architecture or even standard three layer architectures, it is a good principle to keep external access in separate blocks or layers. This opens up for stating that layers or blocks that have no external access should not use untyped or weakly typed data. Layers that do so, should be thought of as having two distinct areas of code, code with untyped/weakly typed code, and the rest should be strongly typed, and one should avoid mixing the two.

A type safe boundary

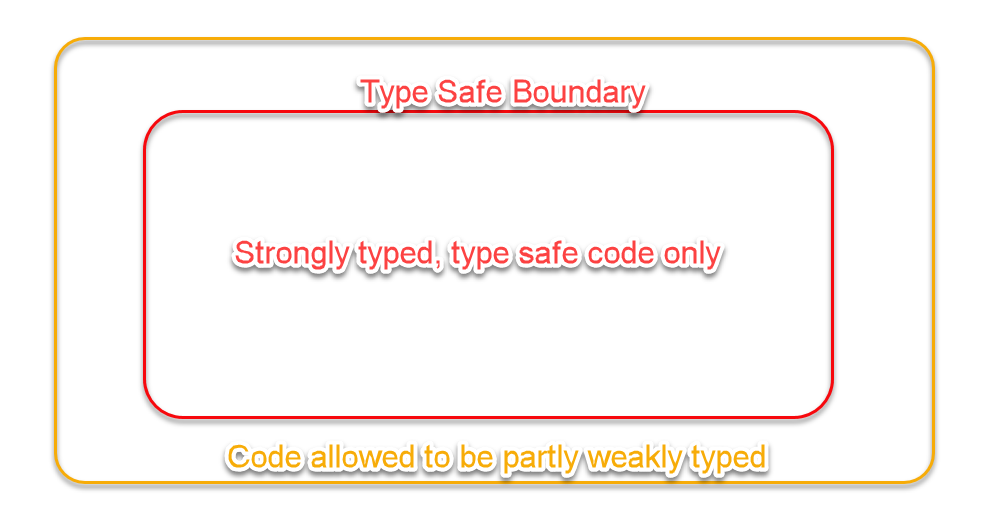

When we make a clear distinction between code that is strongly typed, and code that is weakly typed, one can imagine there being a boundary between the two - that is the Type Safe Boundary.

Within the Type Safe Boundary no untyped or weakly typed code is allowed. Any such code has to go outside the boundary, and has to be contained there.

The role of the code outside the boundary

That also mean that the objective of the code outside the type safe boundary is to convert between the external untyped world and the inside type safe world. For incoming information, the code should convert that information as efficiently as possible into strongly typed structures. For outgoing information, it converts from strongly typed structures into untyped information.

The way this is done is to think around serialization and de-serialization.

As an example, we can look at the way Asp.Net Core can convert configuration data from the appsettings.json file into strongly typed configuration classes, once you have defined those.

Another example is the way logging configurations are directly consumed by the logging code, without the developer having to do any kind of parsing of that code.

The connection with Domain Driven Design

In Domain Driven Design your system mimic the external world using a set of classes organized according to their real world behavior. Also, the classes themselves should have properties that match what is in the real world.

There will always be some properties and concepts that are technical in their nature. The important thing is to keep them as encapsulated as possible.

How does weakly typed information sneak into Domain classes

There will always be a need to add some technical information in addition to the Domain information, one example is surrogate keys for a database. These often leaks out into the domain classes, or at least into the entity or DTO classes that surrounds everything.

The integer fallacy

public class Person

{

int Id { get; set; }

string SocialSecurityId { get; set; }

string GivenName { get; set; }

string LastName { get; set; }

}

The Id property here is the database Id column, which is set up as a primary unique key. When this is present in the business logic as an instance of this class, it will carry around its Id. The reason for this is that code often uses this id to look it up from elsewhere.

public class SchoolClass

{

List<int> Persons { get; }

}

That is, we store the Id around the code, instead of a reference to the object itself. The example above might seem good enough, but it is breaking the Type Safe Boundary. Using an integer Id to represent the object is a weakly typed way. The integer may have any value, and might or not be an actual object.

Instead use the reference to the object:

public class SchoolClass

{

List<Person> Persons { get; }

}

Using strings to name symbols

Another way weakly typed information sneaks in is more direct, using the name of the class in literal string form, or even disguising it a bit more, using nameof(Person) as a parameter to something.

void SendOutputOf(string classname,object obj);

.....

SendOutputOf("Person",person);

SendOutputOf(nameof(Person),person);

In cases like this, the underlying reason is an attempt to make some kind of generic functionality that should work with multiple types of non-related classes. The obvious remedy is to use generics itself.

void SendOutputOf<T>(T obj);

.....

SendOutputOf(person);

Using objects

The example above also has another indicator of weak typing. That is the presence of object. Whenever this appears inside the Type-Safe Boundary there is a breach.

You handle this my replacing that code with the actual type, or generic method.

But I need to do these conversions

It is fully acceptable to do conversions between untyped and typed structures. The main point is it has to happen outside the type safe boundary. If you think of a typical Onion Architecture, you have to place this code in one of the outer most layers.

Outside type safe boundary

The main purpose of the code outside the type safe boundary is to serve the code inside the boundary with fresh new objects, or opposite, deconstruct them into untyped information.

That means we should see serialize and de-serialize code in that area. (And fully covered by tests).

The purpose of the layer is to convert untyped information into typed objects, it serve as object factories.

Unit testing

Errors in type un-safe code can not be detected by the compiler. It circumvents the type checking that the compiler does.

It can be made safer by using unit tests to verify if it works as it should, and does the conversion properly or not.

- Outside the type safe boundary: Unit testing is required, and code coverage should be very high, with a particular focus on type checking.

- Inside the type safe boundary: Unit testing can be more relaxed, and focused on the logical behavior. Type checking is done by the compiler

The Type Safe Boundary as a guide

Code in larger systems tends to get messed up over time, and there might not be enough resources to do proper maintenance. When working with the code, and keeping just the Type Safe Boundary clear in mind, you know better if the code belong one place or the other.

The type safe boundary doesn’t need to be a distinct attribute (folder, project) in the code. It is more like an indication you have in your mind, it is an aspect of the architecture and its layers.

Once you have that clear in mind, you use the Type Safe Boundary concept as a reminder on how you code.

Happy coding!